Welcome back for the fourth installment of the Summer Library Series here at

What She Might Think. This week's reflection is by fiction writer, Dan Powell, and his exploration of books via the library bus that drove into the village of Colwich, in Staffordshire, England. Enjoy!

*

THE LIBRARY THAT DELIVERED

by Dan Powell

I imagined fleets of buses carrying books

to-and-fro across the whole country,

delivering books to every town, to every street.

I thought every library arrived on wheels,

with a heave of diesel fumes and hiss of brakes.

|

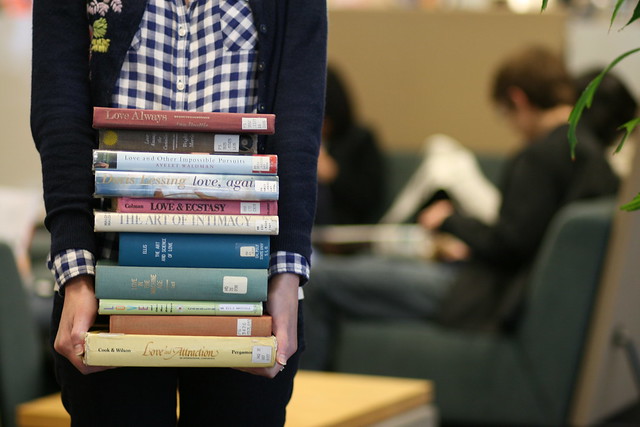

"A Lancet in Disguise"  Claire Pendrous, Claire Pendrous,

Used with photographer's permission |

The library appeared every couple of weeks. Between the end of lunchtime play when the teachers rang handbells to herd us back into class and 3pm when the doors of the school would re-open and we’d pour out onto the playground and spill out the gates, it would materialise in the playground of Colwich School like

The Doctor’s Tardis. Like the Tardis it had the power to take its passengers to any place, to any time, and, again like the Tardis, the books, with whole worlds squeezed between their covers, were somehow bigger on the inside. I always knew when it was coming, yet I never saw it arrive.

For three hours, one day out of every sixty or so, the converted Dennis bus squatted in the corner of the playground where the walls of the Junior building met the railings, the word LIBRARY emblazoned along the side in jaunty green capitals bigger than my head and below that the promise of Books and Information. I was eight years old when I first stepped through the bus’s concertina doors and until the age of thirteen it would be the only library I knew. Inside floor to ceiling shelves filled the space, the clean smell of wood polish and new books fighting and failing to smother the musty aroma of the older titles.

The replacing of cards into covers and the returning of borrower’s tickets took time. No computers then, no bard-coded or magnetized library cards to speed the flow, just a index tray stuffed with the cards from inside the books and the borrowers’ tickets into which the cards were slid. Queuing to return my books, I’d look over the librarian's desk and imagine taking the huge steering wheel behind, driving away with what seemed, to my adolescent eyes, like all the books I might ever need. But I didn’t need to steal the books, given enough time I could simply borrow each and every one. Each of the three child tickets allowed someone my age had the power to take me somewhere beyond the railings of my little school, somewhere beyond the boundaries of the village streets I roamed with friends. I borrowed adventure novels, true-life mysteries, science fiction, science fact, histories and guide books. The little bus, each visit, delivered on its promise. It gave me books and information and so much besides.

I do not remember the names of any of the driver librarians who checked out the books on the bus, who listened patiently to my enquiries, who ordered in the books I pestered for. If I could I would thank them for delivering so much of the world into my eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen year old hands. It was because of them that I learned what kinetic energy was well before it was required of me in school. It was because of them I discovered

Treasure Island and joined

The Secret Seven and survived

The Day of the Triffids. When I had to return two warped and swollen books, damaged in a downpour that flooded my tent while at Cub camp, and I worried they would make me pay for the damage, or worse, revoke my membership, they merely smiled and checked the books back in.

For almost five years this little bus in a little playground of a sleepy Staffordshire village was what I thought all libraries were like. I imagined fleets of buses carrying books to-and-fro across the whole country, delivering books to every town, to every street. I thought every library arrived on wheels, with a heave of diesel fumes and hiss of brakes. Even now, as dazzling as they can be, with their acres of shelving and seemingly limitless stock, I find bricks and mortar libraries somehow lacking. However impressive they might be, for my eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen year old self, they do not deliver. In both senses of the word.

Colwich was too small a village for a branch library in the mid-1980s and it still is today. The library van continues to attend to the reading needs of the community,

stopping every three weeks outside the primary school, delivering Books and Information to the community. I haven't been back since my family moved out of the area in the late eighties. My return to the library van is long overdue.

*

Dan Powell is a fiction writer who lives, writes, and raises a family in Germany. His stories have appeared in a number of anthologies as well as literary journals such as Spilling Ink Review,

Staccato, and

Metzen. Most recently, his story "Half-Mown Lawn," was published in the 2012 edition of The Best British Stories (Salt Publishing),

and was also the winner of the 2010 Yeovil Prize.

To stay updated with Powell's work, check out his Facebook page or website.

Please join What She Might Think next Friday for

"A Truant in the Library" by Laura Ellen Scott.